By Joe Mooney

Vast numbers of passenger pigeons thrived for millennia in North America, many of them roosting in our region’s native trees. It seemed impossible that a creature so numerous could be wiped out. What conservation lessons can we learn from this remarkable bird, and what parallels to the plant world can we draw?

Martha is dead,” the Cincinnati Enquirer reported on September 2, 1914. Martha, who had been living at the Cincinnati Zoo for 15 years, was the last living passenger pigeon in the world and an example of a population that once numbered in the billions.

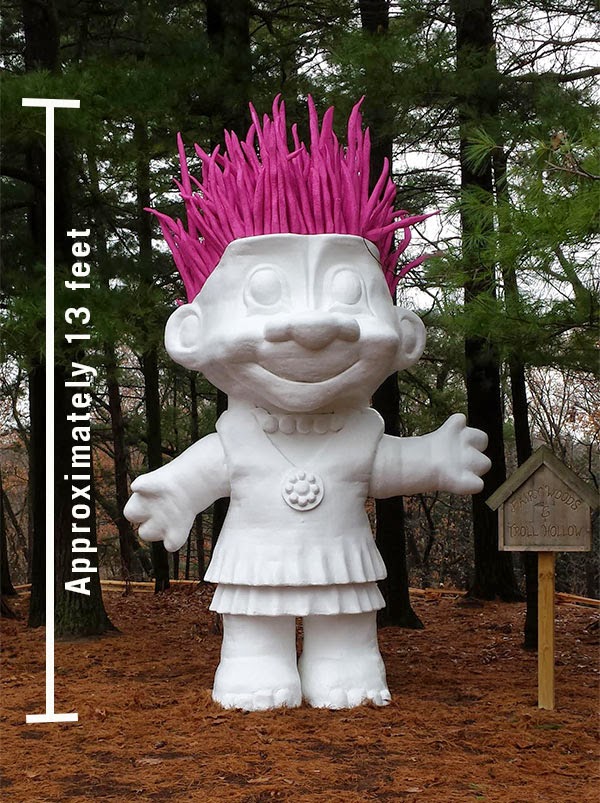

|

| A wood carving of a passenger pigeon by Mike Ford of Midland, Mich. The carving is on display at the Chippewa Nature Canter in Midland. |

By many accounts, passenger pigeons flew overhead in flocks large enough to blot out the sun’s light, or roosted in trees in branch-snapping quantities. John James Audubon himself calculated a flock in Kentucky in 1813 to be more than a billion birds. When Martha died, an entire species died with her.

The passenger pigeon still stands today as one of the largest examples of human action as a major cause of whole-species extinction. The pigeon didn’t stand a chance against the insatiable demand for the birds as food or sport, according to A Passing in Cincinnati, a pamphlet published in 1976 in Washington, D.C., by the Office of Communications, Department of the Interior:

All kinds of firearms were used, but traps and nets claimed the greatest numbers of those mild-mannered birds—often in the hundreds or thousands at one time. They were so numerous in the early 1800s that one farmer once caught more than 2,000 simply by closing the door of his barn after the pigeons flew inside.

American colonists used nets as early as 1640 to take pigeons, and the practice was continued until the pigeon population was virtually exhausted….

Ceaseless slaughter and lack of protection proved the final undoing of the passenger pigeon. By 1886 only two flocks were known to exist. According to A Passing in Cincinnati, in the late 1890s and early 1900s a few states had enacted laws to protect the pigeon, including Michigan, and some individuals made an effort to save the pigeon, but it was too late.

The University of Chicago sent the Cincinnati Zoo-logical Gardens a female pigeon in 1902. When Martha died in 1914 she was “suspended in water and frozen into three hundred pounds of ice and shipped to the Smithsonian Institution. . . ”

A Cautionary Tale

In his book A Feathered River Across the Sky author Joel Greenberg writes, “Human beings destroyed passenger pigeons almost every time they encountered them, and they used every imaginable device in the process. . . . Whether a concerted effort could have reversed the decline and altered the outcome was a question asked far too late for any attempt to have even been tried. . . . It is hoped that this tragic extinction continues to engage people and to act as a cautionary tale so that it is not repeated.”

The implications of a keystone species—one that disproportionately impacts the structure of the ecosystem as a whole—going extinct is perhaps unknowable, observes Matthaei-Nichols natural areas manager Jeff Plakke.

“Probably the best illustrations of what can happen from over-exploitation in North America are the Dust Bowl and more locally, the Great Michigan Fire,” he says. (The Great Michigan Fire was a series of simultaneous forest fires in Michigan in 1871.) “Extinctions of a single species may be less dramatic, but could easily have cascading effects for centuries or millennia.” Plakke points out that the extirpation of beavers in southeast Michigan through hunting and trapping for pelts well illustrates that cascading effect. “Beavers are a prime example of a keystone species,” he explains. “They selectively harvest trees, build dams in creeks and streams, and create extensive acreages of open wetland communities. They significantly changed the hydrology and development of soils. Numerous species of plants, animals, birds, and insects depended on beaver to literally build these ecosystems.” Passenger pigeons were certainly a keystone species as well, continues Plakke. “Numbering into the billions, the pigeons must have had an enormous impact on the environment through their feeding and the movement of nutrients, nuts, and seeds through their migrations.”

Plant-World Parallels

Sheer numbers and the colorful spectacle of their flight made the passenger pigeon particularly vulnerable to exploitation. While plants don’t move in the same attention-grabbing way as birds and other animals, parallels can be drawn between their decline or demise.

|

| A 225-year-old bur oak tree has lived on what is now the Matthaei Botanical Gardens since George Washginton was president. This tree, which would have been 100 years old in the late 19th centeury, likely provided food and shelter for the passenger pigeon. |

Some groups of plants once constituted entire ecosystems unto themselves. “The prairies and oak openings of North America are good examples of ecosystems that have nearly disappeared,” says Matthaei-Nichols director Bob Grese. “Many of the plants associated with those ecosystems are now quite rare.”

A prairie and savanna management guide prepared by the Michigan Natural Features Inventory for the state DNR wildlife division cites a study estimating that just .02% of the Midwest’s original savanna remains, “declining from around 11 to 13 million acres to just a few hundred acres spread across a dozen states.” The report goes on to say that the loss of savanna in Michigan is most dramatic in the oak openings communities, which have declined from an estimated 900,000 acres to just 3, a loss of 99.9996%.

Some individual plant species are also at risk, notes Grese. “American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) is a good example of a plant popular in herbal medicine that has become quite rare because of over-collecting. It is currently listed as ‘threatened’ in the state of Michigan,” a status that offers some protection for the plant, he says.

University of Michigan students working on a geographic information systems (GIS) “grandfather tree” project several years ago mapped and measured over 50 oaks on the Matthaei property estimated to be more than 200 years old. One bur oak at Matthaei (Quercus macrocarpa, pictured at left) is 45 inches in diameter and approximately 225 years old, according to a method for measuring a tree’s age developed by the International Society of Arboriculture. By that estimation the oak would have already been 100 years old in the late 1800s. It’s very likely that this oak and others on our lands here provided shelter and food to the passenger pigeon.

Parts of a Whole

As the late Burton Barnes, professor in the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment once observed, “we are parts dependent on the whole earth for our existence.”

The demise of the passenger pigeon is a graphic reminder of the drastic impacts humans can have on the environment, says Grese. “To know that the most plentiful bird species in North America and the one most associated with the oak forests and oak openings of southern Michigan could go extinct within 100 years is a humbling reminder of the need for conservation.”

As we become more aware of the rare plant and animal species found on the properties managed by Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum we are working hard to steward the unique habitats that contain them, Grese continues, so “creating a greater understanding of the threats rare species and regional ecosystems face is clearly something key for an arboretum and botanical garden like us.”

Exhibits & Resources

Museums and institutions on the U-M campus and elsewhere in Michigan are commemorating the 100th anniversary of the death of the last passenger pigeon with special exhibits and displays. In the botanical realm, for an immersive experience of some of the special spaces that protect or recreate the region’s rare or threatened habitats and ecosystems, such as prairies or the Great Lakes Gardens, visit Matthaei Botanical Gardens & Nichols Arboretum. For a map of some of our “grandfather” trees, visit mbgna.umich.edu. Following is a list of organizations featuring passenger pigeon exhibits. For a full list, visit passengerpigeon.org and click on Michigan.

Passenger pigeon exhibits:

Passenger Pigeon Exhibit: University of Michigan Museum of Natural History, Fourth Floor Gallery

Moving Targets: Passenger Pigeon Portrait Gallery, Enviro Art Gallery, University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment, Dana Building

They Passed Like a Cloud: Extinction and the Passenger Pigeon

Michigan State University Museum

Recommended reading:

A Feathered River Across the Sky, by Joel Greenberg (Bloomsbury)

Passenger Pigeons: Gone Forever, by Vic Eichler (Shantimira)

Online Resources:

passengerpigeon.org, an international effort to familiarize people with the history of the passenger pigeon and its extinction, raise awareness of how the issue of extinction is relevant to the 21st century, and support respectful relationships with other species.

.jpg)